To many, this is still the question. We all know this practice. Make some time estimate, then pad it to compensate for... Actually for what not? Overloading, distractions, interruptions, pressure to speed up work, Murphy's Low and what not. Actually, one more: the inability of the programmer to do good estimates in the first place. Even the programmers admit that they are over-optimistic and that their time estimates are always too short.

This typical predicament is nicely expressed in Rita Mulcahy's book, PMP Exam Prep:

"I have no Idea how long it will take. I do not even know what I am being asked to do. So, what do I say? I will make my best guess and double it!"

In general, padding is bad. Again, as Rita explains it, "Padding is a sign of poor project management!". if you are not sure about your team's time estimates, you should treat is as a risk and not camouflage it as hidden padding.

Actually, why is it bad to pad? Here are several reasons:

- Padding means that there is an inherent deficiency in the estimation (and likely in the estimator's skill). By padding, we disguise the problem instead of facing it and dealing with it.

- When the resource sees their padded tasks, they naturally assume that their task completion date is the one that includes the pad. You are giving the resource "extra time" before they even started the task.

- Once padded, the original estimation disappears. There is no way to hold the estimator accountable for their original estimates.

So, what do we, PMs, do? We know that if we take the estimators' input "at face value" we are most likely in trouble right from the first moment of the project. There are all kinds of things that a Project Manager can (and should) do to improve the situation. None of them is a magic bullet but in combination, they can improve things significantly. Here are some suggestions:

- Give them more time. One of the most compromising factors is the time that we (don't) give to the estimator. If we ask the estimator to estimate a task and want an answer right then, we may assume that the estimator is just throwing a number in the air to get us off their back. Give them time and encourage them to use it to think more carefully and wisely.

- Review the estimates with a critical eye. If you have experience in time estimation and in SW development, you can identify cases where the estimation doesn't seem right.

- Let an expert review. An expert will be able to provide a lot of insight.

- Train the estimator in time-estimation techniques. There are techniques for estimating time. verify that the estimators use them.

- Remind them of the implied sub-tasks. Remind the estimator that there are typically several activities included in a single programming task. Once the programmer realizes that, he/she will benefit in 2 ways: It will be easier to make a more accurate estimation and it will help them remember to do all of these things

- Some thinking, planning, designing.

- Prototyping

- Implementing

- Developing unit tests

- Unit-testing

- Fixing bugs.

All the above are things that the estimator can do to improve their estimates. But there are also a couple of things that you, the Project Manager, can do.

Estimate Effort, not Duration

Estimators easily fall in this trap. They think in terms of duration rather than effort. This automatically introduces padding into the estimation process. You need to make sure they provide their estimates as effort. You usually will have to coach them on this and continuously verify that the numbers they give you are indeed effort and not duration. Estimates in duration muddy the waters.

Nobody Ever Works at Full Load

No human being executes their tasks at 100% of their time. People are human beings. They take breaks, rest, take care of administrative things, go to the doctor, etc. When an estimator provides an estimation of the effort, the number should reflect continuous, non-stop work. In real life, this never happens. Project Management SW tools allow you to specify the load level of the resource. I usually set the load of Individual Contributors to 80% and of Managers to 50%. Granted, this is probably a form of padding but it does not come from uncertainty in the estimate but rather from sound experience. It's not an uncertainty, it's a certainty that people do not perform at 100%. The only uncertainty is the actual percentage. This is up to you to estimate.

Add Project-Level Buffers

This is a mechanism that I invented years ago, only to learn that it was a standard element in Critical Chain Management. I found it extremely powerful even if I don't use Critical Chain Management. Here is how it works:

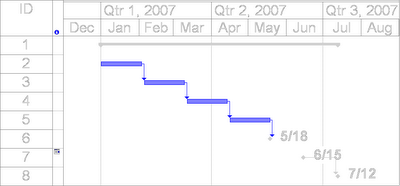

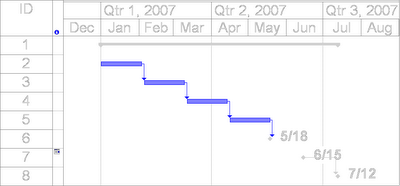

The Gantt chart shows a project with a series of tasks (in Blue). At the end of the project, I added 3 Milestones:

- Optimistic. This is when all the tasks are complete. No buffers, no padding. In the chart it is on 5/18.

- Realistic. This is a date I got by adding 20% to the total duration of the project (from day 1 to the Optimistic milestone). In the chart it is on 6/15.

- Pessimistic. This is a date I got by adding 40% to the total duration of the project (from day 1 to the Optimistic milestone). In the chart it is on 7/12.

As the project progresses a delay may develop in the project end-date. This will cause the first (Optimistic) milestone to move to the right. The other 2 milestones never move. This way we can see how the current projected end-date moves relative to the buffers. In other words, how much of the buffers is being consumed by the delay. This is an excellent indicator that allows the PM to see "how bad things are" and decide if it's time to take some corrective actions.

These are my safety buffers. Generally, I prefer not to show the 3 buffers to my team members. I only show the Optimistic milestone and do not even call it Optimistic. As far as they are concerned, that is the target date that they need to hit. The 3 milestones are for the people that I am accountable to: My manager, the project sponsor, the executives and the customer. I explain these milestones to them as follows:

- Optimistic. We will finish the project on this date only if everything goes perfectly. No delays, no surprises. This is the ideal end date. I have a low level of confidence in this date but I am going to drive the project to this date and try to hit it.

- Realistic. I think this is the date that I can realistically hit and I recommend that you assume and make your plans to this date. I have a good level of confidence in this date.

- Pessimistic. This is the day we will be done if many things go really wrong. I have a high level of confidence in this date.

- If the project runs later than the Pessimistic milestone, something is really bad in the project and we need to reevaluate the entire project.

I used this approach in the past with great success. Managers and customers were very impressed and pleased with this approach. They stopped being fixated on a single delivery date. Now the project is not held by its throat to a single date. There is flexibility but it's OK with management and customers because it is not open-ended. It is bounded. They accept the fact that I do not commit to a single date because they know it's not realistic but they are not worried that I open the door to a runaway project because the end date has a reasonable range.

Let me know what you think...

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------